What If Rob Reiner Survived? Inside the Aftermath No One Talks About

Right now the Rob Reiner case fits a script the public understands. An adult son is charged with killing his parents. There is a long history of addiction and rehab. There is a knife. There are two bodies in a Brentwood home. Prosecutors talk about first degree murder and special circumstances, and he sits in custody with no bail. That is the version you see on TV.

No one talks about the version where Rob survives.

I pay attention to that version because I am one of the very few fathers in this country who survived an intrafamily stabbing by a juvenile family member. I cannot name him here because of juvenile privacy laws, but that experience shapes how I look at what would have happened if Rob had lived.

Parricide is rare and hard to predict

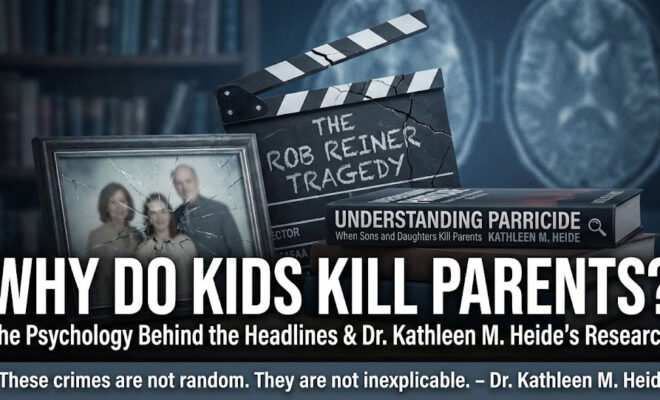

Before we drag this into easy explanations, it is worth listening to the person who has probably spent more time on this than anyone. I have been talking about this person a lot lately and for goof reason.

Dr Kathleen Heide is one of the leading experts in the world on parricide, the killing of parents by their children. The University of South Florida describes her as a leading expert on juvenile homicide and parricide with more than 150 publications and four books on the subject.

In a CBS “Q and A”, she said something that should be written in bold across every article about these cases:

“It is not possible to predict that a particular boy or girl will kill a parent.” – Dr. Kathleen Heide

She explains why. Parricide is statistically unusual. In 2010, out of 12,996 homicide victims with a known victim offender relationship, 107 were mothers and 135 were fathers killed by their biological children. You can see the pattern. It happens. It is real. It is rare. I live inside that tiny percentage now. I am the father in a small city who survived a knife attack by a juvenile family member. When you land in a category that small, you learn quickly how little the public really understands about it.

What Heide actually says about “why kids kill parents”

Heide’s whole career has been spent trying to move this conversation away from sensational headlines and into real analysis. In her work, she groups parricide offenders into broad types, like abused children, severely mentally ill offenders, and those with antisocial personality traits or severe rage toward a parent. These are not excuses. They are patterns.

They are supposed to help courts and professionals understand what they are looking at, not give podcasters and comment sections an easy villain.

If Rob had survived, this is the lens his case would have been forced through. Experts would have debated what “type” applied. People would have looked for abuse that was never reported, for mental illness that was never properly treated, for antisocial traits that fit a neat story.

In my own situation, I watched professionals do something much simpler and more dangerous. They decided they already knew the story and then wrote reports to match it. That is not science. That is confirmation bias in a suit.

Addiction gives the public an easy story

The Reiner case comes with a ready made narrative. Everyone already knows that Nick struggled with heroin and cocaine. Reporting has described him cycling through rehab programs, dealing with homelessness, then co writing Being Charlie with his father, a film based on his addiction.

Addiction history makes people feel like the ending was baked in. For the public, that is the quick explanation. For lazy analysis, it is the perfect scapegoat.

Heide’s work says what people do not want to hear. Risk factors are not destiny. She has spent years tracing how a small percentage of families end up in this extreme outcome, and she still says you cannot predict which specific child will kill which specific parent.

In my case, there was no heroin. No crack. No long criminal record. No long history of police calls. Yet here I am, part of that rare statistic group that was never supposed to exist.

That is one of the first things people around you do when something like this happens. They start looking for the thing that explains it away. The drug. The diagnosis. The secret life. Anything that lets them believe it could not possibly happen in a “normal” family. They do not like hearing that rare things sometimes happen in ordinary homes.

What survival does to the story

When the parent dies, the story is clean, at least on paper.

- The victim is gone.

- The defendant is charged.

- The case belongs to the state.

When the parent survives, the story gets messy. You now have a parent who is a victim and a witness and still a parent. The system does not know what to do with that mix. Courts and agencies are built to deal with offenses, not with complicated, ongoing relationships.

In my life, I saw it immediately. I was treated as someone to “manage,” not as the person who actually lived through the event. My preferences were politely noted, then quietly ignored. That is what happens when survival gives you an opinion the system does not want to build around. If Rob Reiner had lived, the same thing would have happened to him. He would have been pulled into a process that looks like it is about his safety but is really about the system keeping control.

The question that turns back on the parent

The question that turns back on the parent

Once survival is part of the picture, people start asking one question, even if they never say it out loud.

What did the parent do to cause this?

- They look at how strict or lenient you were.

- They dig through therapy histories.

- They study your reactions at public events.

- They weigh every decision you ever made as a mother or father.

This is where Heide’s data matters a lot. In one review, she and others noted that parricide accounts for around 2 percent of homicides and that most cases involve sons, with fathers slightly more likely to be victims. Two percent is not “this happens all the time.” It is not “you should have seen it coming.” It is “this almost never happens and when it does, everyone looks for tidy answers that do not actually exist.”

As a surviving parent, you feel that pressure. In a small city, you feel it magnified. People know something happened. They do not know the sealed details. So they fill in the blanks from their own fears and biases. Heide’s statistics say you are living through a rare event. The community’s instinct is to put you on trial for it.

What the system usually does with surviving parents

If you strip away the emotional language and look at the machinery, the pattern is simple.

- The system knows how to do separation.

- The system knows how to do restrictions.

- The system knows how to do conditions and supervision.

It does not know how to do a parent who says some version of this:

- I survived.

- I forgave.

- I want to rebuild some form of connection with my juvenile family member.

In my own case, I forgave instantly. He is a juvenile family member I still care about deeply. Juvenile privacy laws block me from saying more. The system says I am being “protected” from him. I did not ask for that protection. I am actively trying to reconnect, and the loudest pushback I get is not from him. It is from the institutions that claim they are keeping me safe.

If Rob had recovered from stab wounds and said, publicly or privately, that he did not want his child thrown away forever, I do not think the system would have nodded and adjusted. I think it would have quietly labeled that feeling as a risk factor and moved to work around him.

That is what Heide’s work circles around without always saying in plain language. Courts want stable categories. Real people do not always fit them.

Why this version never makes the news

Why this version never makes the news

The public gets the easy version of these cases.

- Police tape.

- Press conferences.

- Charges.

- Victim tributes.

- Speculation about motive.

The quiet version looks nothing like that. The quiet version is hearings that are often closed. Evaluations written in careful language. Restrictions written “for safety” that also erase the voice of the person who was actually stabbed. Years of trying to correct records that were built more on theory than on verified history.

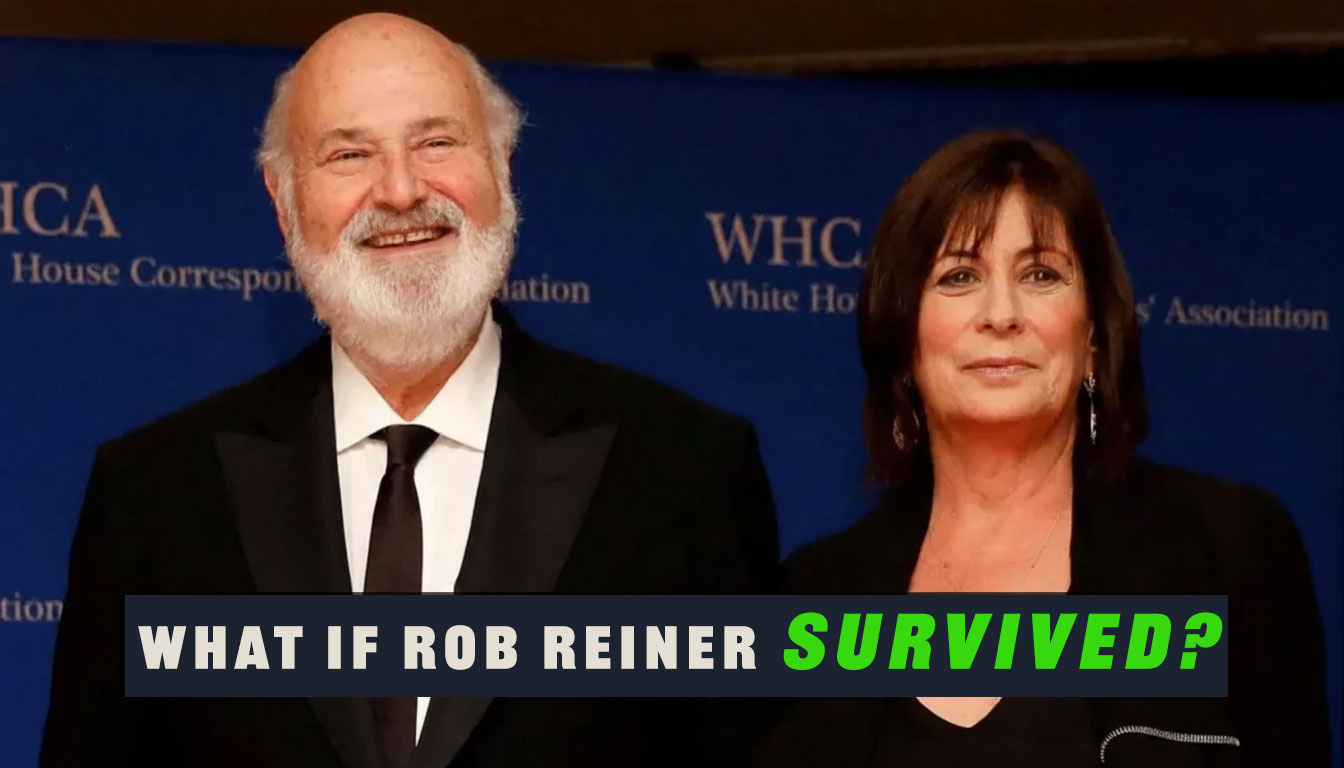

Rob and Michele Reiner did not get that quiet version. Their story ended on the floor of their Brentwood home.

If Rob had lived, he would have stepped into that world. The one very few people see. The one where you are both the object of sympathy and the subject of suspicion. The one where forgiveness and nuance are treated as problems to manage. I know that world too well.

Why imagining survival matters

This is not about softening what happened. Two people are dead who should still be alive. A family is shattered. Nothing about that is up for debate. The point of imagining survival is to make something clear. If Rob Reiner had survived, the story would not have become simpler. It would have become more complicated, more bureaucratic, and more uncomfortable for everyone who likes easy answers.

Dr Kathleen Heide’s work gives the facts. Parricide is rare. It is hard to predict. It usually sits at the intersection of multiple stresses and histories, not one simple cause. My experience adds one more piece. Surviving a stabbing by a juvenile family member does not give you control over the story. It puts you in the middle of a machine that was never designed to respect your forgiveness or your instinct to stay connected.

The public sees the headline version of these cases. The surviving parent lives the other version. And in most conversations, that version is missing.